By Sara Bass

Edited by Michele Carlo

In a time of forced patience, our lives slowly distill into their rudimentary ingredients. By the intention to love and nourish, a local illustrator and watercolorist draws together these ingredients from seemingly disparate lives, glorious in their smallness and evanescence, until nobody feels so unfamiliar anymore.

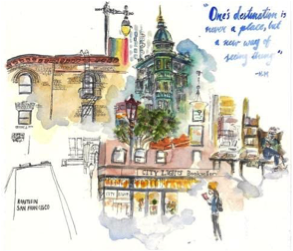

Brooklyn- and San Francisco-based illustrator and watercolorist Shani Zhang is more often concerned with breadth of experience, but when she yields to time slowed down, she finds meaning in depth. She says the most enchanting qualities about New York are its fickleness and its abundance. She finds beauty in the idea of there being so many untouchable spaces that force a decision to be at peace with just the parts one does have capacity to access. A Victoria Erickson quote on the cover of Zhang’s San Francisco sketchbook summarizes the common philosophy of her illustrations: “… to breathe magic into the mundane.” She generates compassion through the simple art of patiently observing the things and lives mostly lost in our peripheries or to our needless urgency that are, at least for those moments, the only reality we have.

In vague watercolor and pen, Zhang’s work renders overheard conversations in cafes, subway stations, and public parks; tender moments in public; and the way the light strikes at a certain time of day. She combines sprawled, unrelated experiences into cohesive moments, trying to capture the essence of life. It’s something she determines in the degree of freedom with which a person carries themselves and shows in their distribution of weight, something nourished by sympathy to how others live, something she looks to the late feminist author and social activist bell hooks for help describing as “love ethic,” something packed into a sliver of time.

Throughout her childhood in New Hampshire, Zhang carried a sketchbook, filling its pages as a means of noticing things she otherwise might not see. After high school, she brought her practice of sketching through moves between Naples, Italy; Siem Reap, Cambodia; and Bir, India. And again, during her time studying at Minerva University, she continued the habit of remaking home every few months; across each changing place and routine, drawing was a constant. In August 2021, Zhang relocated to New York and now splits her time between Brooklyn and San Francisco. When she first started filtering her experiences through paint, she wanted to raise her own awareness to the ordinary. As the Covid-19 pandemic began in early 2020, she recognized a new purpose in art that harkened back to the Edgar Degas quote on her old art studio’s door: “Art is not what you see, but what you make others see.”

When Covid-19 became a global emergency, Zhang was living in Buenos Aires. Under a government-enforced lockdown, nobody in the city was allowed to leave home except for essential reasons. She remembers the only people in public during that time were the city’s houseless, and with many hours newly freed, she’d spend much of her days watching them in the plaza through her window. She noticed them shift from one bench to another, stand around aimlessly, and go without the tossed take-out food that was no longer as available without the plaza’s regular foot-traffic. She made a practice of “good staring,” something she learned from Garland Thomson’s book, Staring. It explains how photography can facilitate empathy and a possible response of benevolent political action on behalf of marginalized communities if practiced with good staring. Bad staring, alternately, looks without recognizing and draws distance.

Zhang channeled her compassion for those below her window into illustrations that led her to make and deliver care packages of sandwiches and water bottles. After posting her drawings on Minerva University’s Facebook page, she received comments from classmates asking how they could help either with the care packages or by donating money.

Another source that informs Zhang’s artistic approach is a series of paintings by Chris Rush that captures individuals with Down syndrome in a more dignified light than is typically cast. She aims to do something similar with each of her pieces by combining moments of stillness with good staring amid the mundane, as if to generate the magic of widespread compassion sandwiched between two slices of bread. “We create things to save ourselves,” said one of Zhang’s classmates in a letter written to her after graduation. Zhang says, “We create things to save each other. In the modern cities we live in, one of the worst things to feel is to feel alone, and art is a promising way of shattering that aloneness.”

![]()

Lately, Zhang has been consumed by thoughts of love. She’s not satisfied with the description of love summed in the hackneyed statement, “it’s something you know when you feel it,” and she’s been taken with the added responsibility bell hooks ascribes to it in All About Love: “To truly love we must learn to mix various ingredients — care, affection, recognition, respect, commitment, and trust, as well as honest and open communication.” This slowed time allows us to hone our ethics of love, being particular about the ingredients that constitute our routines and how we invest in them. In her San Francisco notebook, she distilled this concept of love further into two basic components; painting in bold strokes across a page: “We are what we LOVE. We are that we LOVE.” Another page declares: “Don’t look away, look right at it. This is what your heart looks like.”

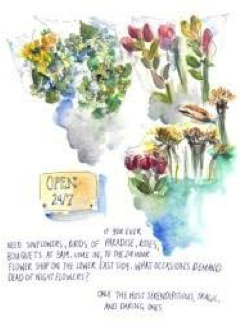

At present, most of Zhang’s work is commissioned, though she still carries her sketchbook to record the sound of water in Manhattan, spectators in Tompkins Square Park, the peculiarity of a flower shop open 24 hours a day, or a little girl responding to buskers requesting compensation with “I think it should be more than a dollar, they’re really good. $2?” She invites us, regardless of the vastness we perceive between our experiences and pandemic-era bodies, to not forget, “reading this again years later that this moment was once your life.”

A selection of Zhang’s work is viewable on her Instagram. For commissioned pieces, contact the artist at her website.